Partners in Crime

If comparison is the thief of joy, expectation is the getaway driver. A little maniac in our minds hopping medians into oncoming traffic and dragging our thoughts and emotions screaming the wrong way down one-way streets. Hitting the e-brake at the last second around hairpin turns that send us careening down blind alleyways. All in the space of a second.

Comparison is useful. We need to be discerning to recognize truth. And expectation is important. We have to set standards for our own well-being. It’s when we set our expectations based on comparisons to others–where they are in life, what they’re doing, the things they have–that things start to get ugly. This includes basing our expectations on the beliefs and opinions of others. Things really get out of hand when our attitudes solidify into desires that we clandestinely foist upon others. Unspoken and unrealistic wishes that go unfulfilled inevitably become resentments. Perhaps worst of all, we treat ourselves and others as objects of sometimes abusive ridicule after failing to live up to what are often delusory standards.

This sort of fraught logic applied to food–what, how, and where we eat–tends to result in bouncing from fad diet to fad diet, binging for fulfillment, or spending absurd amounts of money on pre-packaged foods and dining out driven by convenience. Here are the facts:

- Fad diets are repackaged marketing schemes that exist to separate us from our money. Most require untenable amounts of will power to observe dutifully. None take into account variabilities in individual biology and physiology, lifestyle factors, or various externalities. If we do happen to achieve results they’ll most likely be short-lived, as maintaining an unrealistically stringent dietary plan is unsustainable long-term for most of us. In fact, according to a U.S. Institute of Medicine study on military weight management published in 2004, just one to three percent of individuals who lose weight through dieting alone successfully maintain the loss. Yet the expectation for extremely positive outcomes persists and the cash keeps flowing.

- Binging is usually the result of some unaddressed emotional response to stimulus. Or simple boredom. It’s not healthy for us. Most of us do it. It’s not easy to stop. Yet the expectation is that we should have enormous reserves of self-restraint available to us in avoiding such behavior at all times. In the absence of continuously accessible alternative coping strategies, this is unrealistic. Moments of weakness are bound to crop up. There’s no need to beat ourselves up about it, but we do. counterintuitively, in beating ourselves up we actually reinforce the behavior. At work in this scenario is the expectation that we should never make mistakes.

- A study Published in 2013 by Nutrition Journal indicated that two-thirds of food consumed by Americans on a daily basis comes from at-home sources. Taken at face value, that seems like a good thing. Interestingly, though, most of those calories were consumed as ready-to-eat meals and other processed foods. Foods which typically have low nutritional value. The other one-third of our food comes from eating out at restaurants of all types, with the average American spending $3,459 on away-from-home dining. Consumer culture commodifies our very experience of food, wherein we engage in connection-buying, persona-building, and the pursuit of convenience. We’re not only told how and what to eat by taste-makers and culture warriors, but how best to enjoy what we eat. We see food as a vote by proxy for this or that lifestyle, and we expect others in our circles to conform to our choices. It really separates us from our appreciation of food and from each other. Essentially we’re all becoming affected food snobs, run down fast-foodies, and microwave meal preppers.

Exit the Loop

How do we break these negative thought patterns? To begin with, it’s helpful to base our expectations on simple and realistic criteria rather than getting caught in loops of comparison and expectation. We need to take a different frame of reference for setting our standards. A frame of reference rooted in the four pillars of well-being:

- Flexibility

- Appreciation

- Reflection

- Compassion

The four pillars are essential life tools. They act as the basis for helpful expectations, and they enable us to identify harmful ones. But this presents questions. What is a helpful expectation, and how do I know if my expectations are actually harmful?

Harmful Vs. Helpful Expectations

Mismatches between expectation and output are the proximate cause of almost every one of life’s conflicts, from little disappointments to huge difficulties. We stoke the flames of discontent with unrealistic and unreasonable demands made of ourselves and others. Harmful expectations almost always lead to tension between internal and external reality. To a great extent, they’re extrapolations from real needs and valid desires. Only, the center of gravity is off so that expectation rarely aligns with output.

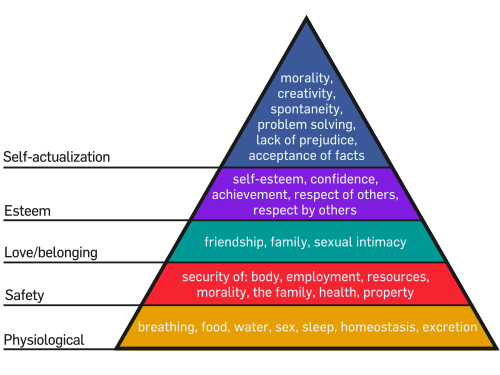

There are clearly some things that are baseline necessities for a happy and healthy life, and we should have a reasonable expectation of having those needs met. They’re normal and natural. They’re most succinctly expressed in Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Most of us learned about them in high school, and they’ve been extensively explored by other writers and thinkers. Without going into too much detail, they’re organized into five broad categories: physiological, safety, love/belonging, esteem, and self-actualization.

The lion’s share of expectations falling into these categories are considered to be healthy and helpful. That is, if they aren’t taken to an illogical extreme and they don’t interfere with our daily lives or the lives of others. Taken to unreasonable lengths they’re limiting. Let’s take something like a demand for perfect safety in all undertakings as an example. Obviously, because it presents us with an impossible-to-meet standard, such a demand is harmful. It should be clear that all activities entail some risk. Therefore, meeting this expectation would require us to limit our range of experience and to stifle the freedoms of those around us. Clearly this makes for a very poor expectation.

For the most part, it’s the exorbitant expectations that we build up around our actual needs that lead to problems. The physiological need for sex is rife with easy examples of this. We may have an expectation/output mismatch with our partner regarding the frequency or timing of intimacy, say. Or we might suppose in an entitled way that someone should be physically attracted to us. Similarly, food and dieting can be a painful source of expectation output mismatches of various kinds. We might believe, for instance, that if we exercise a certain amount we can eat anything we like in greater quantities than we need. For most of us experience says it’s not so. With these examples in mind, if we’re to avoid continual conflict and disappointment we need to identify and correct our harmful expectations.

Identifying Harmful Expectations

Our expectations may be harmful if:

- They are rigid and unyielding to changing circumstances (e.g. the belief that oneself or others should never make mistakes).

- They are seeded by incorrect judgements resulting from magical thinking (e.g., “Person x should understand what I want without me having to tell them directly,” or “people should just be able to do what they’re supposed to do”).

- The expectation is explicitly or implicitly self-negating (e.g., demanding that all risks be eliminated before pursuing any undertaking leads one to pursue nothing at all, as absolute safety can never be guaranteed).

- They preclude the range of acceptable thoughts, feelings, or emotions that can be safely experienced or expressed by oneself or others. (e.g., expecting that others never openly express anger or dissatisfaction).

- The expectation presumes an irrational degree of control over oneself, others, or events and circumstances. (e.g., insisting that one should never be late).

- It routinely leads to disappointment, disenchantment, or depression (e.g., expecting others to always be willing to apologize for perceived slights, or to recognize when we might be offended in any situation).

Any of these six indicators is a sign that your expectation might be harmful. It could be that the expectation is based on erroneous assumptions. Or maybe it unfairly shifts the burden of responsibility for agreeable outcomes to others. Perhaps it’s just wildly unrealistic in and of itself. That said, many of our most poorly conceived expectations follow a particular format.

Blame-Chains

Harmful expectations are often tied to what I call blame-chains. They mostly follow an if/then/should format:

If I, if you, if he, if she, then I, then you, then he, then she, I should, you should, they should. . .”

Blame-chains tend to first crop up as an unspoken internal dialogue. Like a nagging voice in our head that gets us lost in a haze of inaccurate and unjustifiable imputations. This voice represents a version of us that can’t account for life’s nuance and unpredictability. Owing to a lack of perspective, causality is assigned based on spurious assumptions related to the belief that our thoughts alone can influence the world of experience.

Expectations rooted in if/then/should statements are sometimes both counterfactual and overly presumptive. For instance, imagine thinking or saying of your partner, “if only we hadn’t eaten late so often, then I wouldn’t have gained so much weight.” Such statements counterfactually reduce our weight problem to just a single cause, not taking into account our full spectrum of behavior and circumstance. They also shift some of the responsibility for our actions to our partner. Taking things a step further we might add, “my partner really should be able to prepare dinner earlier.” Now we’re imposing an additional unfair burden of responsibility onto them by suggesting that they should somehow just know better.

If we’re to set helpful expectations it’s important to retune our perspective. For a start, we have to learn to let go of the idea that simply wishing something will happen, however sincerely, will make it so. Secondly, we have to relinquish the notion that brutishly imposing our will on others will cause them to conform to our expectations. This includes changing our attitude toward ourselves. Let’s compare some harmful versus helpful expectations and think about which ones might lead to more favorable outcomes.

Examples of Harmful Vs. Helpful Expectations – Life and Relationships

| Harmful Expectation | Helpful Expectation |

|---|---|

| Expecting external physical stimulus to be a constantly available source of pleasure and comfort | Receiving simple pleasures with appreciation, in moderation, as they come |

| Expecting that a single individual, group, or undertaking will fulfill all of our emotional needs | Cultivating many sources of emotional fulfillment and joy |

| Expecting never to have to deal with conflict | Trusting that when conflicts arise we will have the resources to deal with them appropriately |

| Expecting that our choices and actions bear no consequences | Accepting that every choice/action comes with a set of outcomes and opportunity costs |

| Expecting that things will always be the way they have been | Understanding and accepting that every situation, good or bad, is subject to change |

Examples of Harmful Vs. Helpful Expectations – Food and Dieting

| Harmful Expectation | Helpful Expectation |

|---|---|

| Expecting others to anticipate or attend to our dietary needs in every situation | Planning ahead to assure that we can meet our personal needs based on the situation |

| Expecting food to act as a salve for emotional distress | Learning to deal with our emotions directly and honestly without using food as a coping mechanism |

| Expecting every meal to be a special event | Enjoying simple food and drink that meets our dietary standards |

| Expecting others to wait for us to photograph and make a show of our food every time we gather to eat | Respectfully enjoying the company of others while allowing opportunities for photography to present themselves organically |

Which expectations seem more likely to increase our feelings of well-being? It’s obvious that the expectations on the right are the least limiting. Their formulation enables us to meet our own needs without placing too many conditions on others. Also, they don’t require us to box ourselves into rigid and unsustainable patterns of behavior. Of course, everyone’s sense of well-being is somewhat unique to them. So how do we define well-being?

What’s Well-Being?

Well-being is a kind of a poncy word for feeling good. Kidding. Our sense of well-being encompasses our overall mental health. Not necessarily straightforward feelings of pleasure or temporary satisfaction. Life fulfillment and our ability to manage and deal with stress are major factors contributing to our well-being. This entails feeling secure in ourselves emotionally and physically. Having a sense of safety in our communities. And experiencing some autonomy in our work.

There are numerous factors that contribute to or detract from our well-being in each of these categories. Many are individually specific. It would be impossible to list them all. That’s why it’s important that we each think deeply about what well-being entails for us. Let’s focus on just four simple tools that we can use to shape our thinking about well-being and expectation. Flexibility, appreciation, reflection, and compassion. The four pillars of well-being.

The Four Pillars of Well-Being

Four foundations, four remedies, and now four pillars? Yeah, pillars. . .four of them. I know it might seem hokey, but these four tools are essential in setting clear and realistic expectations for ourselves and our lives. When we slowly and patiently incorporate them into our way of thinking we gain clarity and insight into our own well-being and that of others. Instead of feeling blown around in life like leaves in the wind. Drifting from one event happening to us to another, then another, then another. We come to feel like empowered agents in our own existence, able to affect change and influence the course of things. We achieve this by learning to focus on matters over which we can exercise a reasonable amount of control, and by letting go of judgments that place our own ego at the center of everything. Let’s take them on one at a time.

Flexibility

Just as physical flexibility is a skill that takes patience and effort to achieve, so too is mental flexibility. Some of us are more naturally mentally flexible than others, but it’s something everyone can learn to improve with training. This skill is our number one pillar because it’s important to understand that our expectations need to change based on the situation. A flexible mindset is the critical factor influencing our motivation, determination, and drive. In fact, some research indicates that increased cognitive flexibility may play a role in decreasing anxiety and depression. Think of this quality as the mental agility that helps us to quickly move away from limiting thought patterns. We’ll need this skill to put the next three pillars into practice . Here are some tips for working on your mental flexibility:

- Change up your daily routine now and again. Nothing drastic, just minor changes here and there that allow for spontaneity. Perhaps you might take a new route home from work, or take a different path on your daily walk. This opens us up to new possibilities and forces us to deal with unexpected events that will challenge us to think differently.

- Try to introduce little difficulties into your daily activities. It might be something simple. For instance, using a pen and paper to write your shopping list so that you can’t rely on automatic spell-checking and reminders. This might seem ineffectual, but adding small challenges to daily activities forces us to rely upon internal resources to solve problems. In theory it also loosens up our expectations for perfection.

- Meet new people who aren’t like you. Then, gasp, try to make friends with them. Nothing jolts and jostles our expectations more completely than interacting with people from different cultural, political, social and religious backgrounds.

- Travel without an itinerary. Going to a new place and letting things happen as they happen can be a little scary at first. Once you get your feet wet you’ll want to go itinerary-free on every trip. It can be less stressful, and it gets us used to allowing the events of the day to flow naturally.

- Show up late. Of course, there are times when this might be inappropriate. You don’t want to stroll into a job interview 30-minutes past due. But most of the time whatever schedule we’re on is either self-imposed or not urgent. Slip off the leash and give yourself permission to take it slow now and again. Things will get along fine without you for a little while.

- Play a new game. Research into the effects of real-time strategy gaming on cognitive flexibility, published in Plos One in 2013, drew a positive correlation between certain types of games and cognitive enhancement. I like the RTS game Northgard for Nintendo Switch. While the positive effects were only noted in association with complex RTS-style games, it might also be useful to play puzzle-style games as well. The puzzle game TanZen for iOS is one of my favorites.

- Become a lifelong learner. Whether it’s reading more non-fiction, taking up a new hobby, or learning a new language. Evidence suggests that lifelong learning is beneficial for cognitive flexibility and overall well-being.

Appreciation

Appreciation is absolutely vital to well-being. If we’re to improve our lives and correct incorrect perceptions then we have to start by being grateful for what we have. After all, if we choose a life devoid of gratitude, taking everything for granted, then life is meaningless. But by appreciation I don’t just mean gratitude. I mean learning to develop abstract understanding of where we are, what we have, and what’s possible. Really assimilating our present situation into our consciousness. If we’re unable to fully appreciate the reality of our current place in the world then we’re stuck there. We can’t extrapolate properly and our expectations stagnate. Lack of both types of appreciation represent a failure of imagination. Both lead to destructive patterns of expectation and outcome.

Take dieting as an example. Most of us are under the impression that modifying our diet will lead to a physical transformation very quickly. We see startling images depicting before and after results of this or another fad diet or workout program on social media and expect the same outcomes over night. When we don’t see drastic results according to our arbitrary timeline we slow down or give up entirely. But here’s the thing: what we see on social media are often the results of marketing magic. I know this first hand because I’ve spent 15 years making that magic happen. Let me tell you, the rabbit was in that hat the whole time. This is an expectation/output mismatch due to a flaw in our appreciation.

In order to make real progress we have to appreciate (that is, realistically understand) where we are so we can get where we want to go. We all start someplace. We all end up someplace slightly different. Get comfortable with both of those things and you’ll be more likely to succeed in whatever it is you do. Secondly, we have to appreciate (that is, have gratitude for) small victories. Gratitude is powerful. Find something, anything, to feel thankful for. It will change the way you view yourself, others, and the world around you.

Here are some tips for working on your appreciation:

- Take a self-assessment to identify your strengths and weaknesses. Then focus on your strengths. I really like StrengthsFinder. Chef Ngoc and I have benefited a great deal from taking it together, and we both stand by it as a general guide. Every self-assessment has its flaws so choose whichever one suits you.

- Write a note to yourself realistically outlining where you are now and detailing a set of workable expectations for the future. Be honest, truly base these on your current situation as a starting point. Remember, everything takes time, no matter where you begin. Don’t become discouraged. Point yourself in a direction and walk.

- Keep track of your progress. Make note of milestones.

- This might sound weird, but sign a little contract with yourself not to complain for one week. Have a friend or family member countersign it and agree to hold you accountable. If you keep the contract you’re going to feel better. Guaranteed. Compare contract you with no-contract you for a real dose of reality. I’ve done it. It’s striking.

- Try counterbalancing one negative thought with two positive ones. Seems trite, but it works.

- Write “thank you” notes. People appreciate being recognized unexpectedly. It’s just a nice thing to do. You’re gonna feel good.

- When you wake up in the morning, or right before you go to bed, write down one thing you’re thankful for. Anything at all.

- Make time every single day to remember that one day you will die. I keep a skull inscribed with the words “Statim Finis” on my desk. When I feel like being a jerk or I’m being particularly lackadaisical, I look at it and it fills me with a sense of determination to make the most of myself. I’m also filled with gratitude for the time I’ve had and the time left to me.

Reflection

Thinking deeply about our own expectations and actions is such an important thing. It’s significance as a core component of mindfulness practice simply can’t be overstated. Through reflection we develop the wisdom and insight necessary to adopt healthier ways of relating to ourselves and others. Many of our expectations are predicated on our own negative labels for certain standards of behavior or ways of thinking and doing. By making a committed effort to moderate and change our antipathetic judgments we open ourselves up to differing viewpoints about the world. We also affirm the uniqueness of perspective we each possess.

In this practice we take the time, just a few minutes or so each day, to think through the events of the day. Maybe by writing them down and identifying times when our expectations weren’t met in the way we anticipated. Being honest with ourselves as to whether or not the expectation was a realistic one. Not judging or pummeling ourselves if we find that the expectation wasn’t realistic. We just note it with curiosity and understanding. Over time, as these expectations arise again, we can begin to catch them in the moment and make a mental note. Something like, “here’s this one again, how funny that I feel this way sometimes.” The idea is to get to a place where we can observe, in a loving and non-judgmental way, hyperbolic thinking that skews our expectations of ourselves and others.

Here are some ways to reflect throughout the day:

- Keep a private journal.

- Begin a daily meditation practice. Try this guided meditation.

- Find a private place and speak your unmet expectation out loud. Sometimes giving voice to something helps us to realize when we’re truly being unreasonable with ourselves or others.

- Calm yourself by taking a long walk at a slow to medium pace, allowing yourself to feel whatever you’re feeling as it arises. When you notice that your emotions have evened a little, see if you can sit and examine the contents of your thinking with some critical distance.

- Record your thoughts and feelings using the audio app on your phone, then play it back to yourself when you’re feeling calm and collected. Once you’ve listened to it completely, delete it as an act of letting go.

Compassion

No act of kindness, no matter how small, is ever wasted.”

– Aesop, The Lion and the Mouse

As a child one of my favorite things to do was to read Aesop’s Fables. From what I remember it was a beautiful old hardbound edition from the 1920’s with a stately-looking fox on the cover doffing his hat to a matronly lamb. Being a smallish-for-my-age and easily underestimated introvert at the time, the fable of The Lion and the Mouse really struck a chord with me. I’d tear up at every reading, sniffling and sometimes sobbing at the tale. Not because the story was particularly sad. But because of the fearless compassion of that tiny mouse.

You see, the lion thought of the mouse as a weak little nobody. But the mouse refused to see herself that way. She didn’t let the lion’s limiting definitions of what and how a mouse should be prevent her from seeing herself as capable, or even of acting bravely in the face of great danger. The little mouse’s self-compassion allowed her to behave compassionately toward others. And her broad sense of empathic love didn’t limit her view of the lion to one of a brutishly mindless killing machine. In his moment of weakness the mouse saw the lion for what he was, a fearful fellow being in need of help. I found strength and beauty in that and it made me cry. All these years later I’m still inspired by that ancient story and I revisit it often.

What I take away from the fable is this: Be kind to yourself. In being kind to ourselves we unlock the capacity to show genuine kindness to others. Our view becomes widened and less limiting. Also, when we contrive circumscribed narratives about the motivations or capabilities of others (ourselves as well) we blind ourselves to the qualities that are really there, and perhaps risk missing out on opportunities for connection. We all have a fabled lion and mouse inside of us. Temper the lion. Tune the mouse. Practice patience, openness, and gentleness with yourself and others.

You might be wondering, “compassion, that’s great, but how is this in any way related to food?” Good question. When was the last time you kicked your own ass, mentally that is, because of some failure related to dieting? Or a time you may have given up on cooking or baking because your end result didn’t look or taste the way you thought it should? How about getting a quiet taste of sweet schadenfreude at the dieting failures of friends or family members? All are lapses in compassion resulting from untrue beliefs about ourselves and others. All are limiting and demotivating. Personal progress requires compassion, especially self-compassion. In fact, a meta analysis published in 2015 pointed to self-compassion as a key correlate of higher individual well-being. Give a little. Get a little. And grow.

This doesn’t mean manufacturing a mawkish or saccharine air of feigned concern, or one of patronizing pity. It also doesn’t mean we should attempt to downplay, ignore, or make excuses for our own shitty behavior or the shitty behavior of others. It means that we gradually learn to accept these things as part of the human experience while cultivating a growth mindset over a fixed mindset. We’re not trying to force anything here.

As an example, I had a very rough relationship with my adopted parents. Both had drug and alcohol problems. Both were physically and emotionally abusive. Their behavior throughout my life was, for lack of a softer term, fucked up. Absolutely unconscionable. Over time I’ve been able to cultivate a genuine sense of compassion for their negative life experiences, which fills me with a sense of sympathy rather than hatred. I’ve been able to forgive them in some ways, but without making any excuses or special cases for the damage their actions have caused.

I’m not perfect, there are many things I’m not willing or able to forgive at this point in my life. Some wounds just don’t heal with time. I accept that fact about myself with self-compassion, understanding that it doesn’t make me a bad person. Leaving room for myself to perhaps forgive in the future. Just the same, I don’t wield their shortcomings as a weapon. This would be unfair. What’s past is past. They’re both dead and I’ve moved on. Compassion for me is in recognizing their hardships. And realizing that were it not for certain fortuitous events in my own life I can imagine myself having slipped down the same dark path they went down.

Here are few methods for cultivating compassion:

- Practice loving-kindness meditation: send good vibes to yourself, a loved one, one who is neutral, and one who is difficult. It’s a straightforward practice that takes about five minutes. Close your eyes and visualize the object (starting with yourself) of the meditation. Repeat the following: “may I be happy, may I be healthy, may I know peace.” Repeat three times, slowly and sincerely. Move on to the next object, replacing “I” with “you”. You’re not trying to influence or do anything in particular, this isn’t about magical thinking. You’re just letting feelings of empathy and support flow naturally, even simply noting a lack of them.

- Give yourself a break when you make a mistake. Kind of how you might treat a little kid. Acknowledge any difficult feelings you might have about the issue and meet the situation with curiosity about what might have led to the mishap. Allow yourself some space to think about how you might realistically improve next time. Instead of using negative labels, describe the situation and the solution using accurate and specific language.

- Use cognitive reframing to view situations differently. Here’s a dietary example: a colleague who may or may not know you’re on a sugar-free diet brings you a doughnut for breakfast. In this situation you might initially be inclined to think, “why would [s]he offer me something like this, doesn’t [s]he know that I’m trying to lose weight?!?!” Instead you might reframe the same behavior in this way, “how kind of them to have been so thoughtful. Even though I can’t eat sugary treats right now it’s nice that they went out of their way to make a friendly gesture.” See the difference? In this way you acknowledge that you’re unable to consume the food, while not negating the kindness of the gesture itself. It’s not about pretending something isn’t what it is. It’s about seeing others charitably, which leads to increased feelings of compassionate joy. You can also use reframing to view things from another’s point of view. This lets us realize that our point of view isn’t the only way to see a problem.

- Communicate your feelings without assigning blame. You’re much more likely to make an impact with your words (even when they’re addressed to yourself) when they don’t contain judgments. This one is difficult to put into practice in the heat of the moment, so be patient with yourself in trying to apply it. Start by trying to eliminate words and phrases like “I always,” “you always,” “they always,” and “every time.” This small semantic step makes a big impact. It shows compassion for yourself and others by conceding that nobody always screws things up every time. It leaves room for you and others to improve upon past behavior, and it doesn’t drag things through the mud in their totality.

So, What’s Next?

We can use the pillars of flexibility, appreciation, reflection, and compassion to keep troublesome expectations from corrupting our thinking and spoiling our joy. But this is just the beginning. Our goal is to use them as a support structure in setting up sound non-negotiables for well-being. Ones that guide our choices and behaviors long-term.

Setting Non-Negotiables

So, what’s a non-negotiable? And isn’t the idea of a non-negotiable incompatible with the ideas we’ve already discussed about expectations? No. It isn’t. The point is that they can’t be wildly unrealistic or unattainable. Non-negotiables are doable and maintainable expectations for our own well-being that we alone, as individuals, are responsible for. Like little contracts with ourselves that we own and execute. We stick to our non-negotiables day in and day out regardless of external factors. As such we have to be honest with ourselves about our own needs and capabilities, and we have to be up-front with others in expressing our standards. But they are our standards, which is important to keep in mind. We don’t impose non-negotiables upon others, we uphold them for ourselves.

For example, you may have an expectation that you must get some form of exercise every day. Say you’re also in a relationship. One where your partner’s expectation for physical activity is less than yours. This is a pretty common scenario. It can be a source of disagreement and even resentment when the expectation goes unmet on one side, or it’s perceived as a catalyst for coercion and nagging on the other. This expectation is only suitable as a non-negotiable if you take full responsibility for seeing it through without placing any dependencies for your own behavior on your partner (or anyone else). You must accept that your partner’s needs differ from your own. You must also clearly communicate that you will make space each day for your own exercise. They’re welcome to join you if they like.

If you miss a day for whatever reason, it’s on you, not them. And, because exercising is your non-negotiable, instead of making excuses or quitting indefinitely when you have a setback you try again tomorrow. That said, your non-negotiable needs to leave you with sufficient room to adjust your expectations according to circumstance. Perhaps working out every single day just isn’t realistic given your current life situation. Your non-negotiable formulated slightly differently might be: I will make exercise a significant weekly priority. Maybe start with two or three days per week. If you’re able to maintain that behavior consistently you can increase it to four or five days. You might also expand your definition of exercise to include things like gardening or yard work.

Non-negotiables require us to observe all four pillars of well-being. We have to develop flexibility to maintain them over time. It’s important that we exercise appreciation to know what’s possible and to sustain a sense of gratitude and perspective. We practice reflection upon our actions, our progress, and our failures and we plan accordingly. Perhaps most significantly, we show compassion to ourselves and others when things don’t unfold in keeping with those plans. Essentially, the four pillars along with our non-negotiables represent the formalization of a growth mindset. A mindset that helps us to not hide from our struggles, but to instead embrace and learn from them. The key thing is that we place neither onus nor blame on others. Our goal is to learn to see things in terms of their potential based on our current state. Not in terms of a fixed state based on current conditions. Above all else, we choose not to yield our well-being to unhealthy comparisons with those around us.

Little Fires Everywhere

If you want to build a good campfire you begin by placing a bed of tinder within a stone circle. Then you add some kindling above and around your tinder. Finally, you loosely place your logs on the outside of this structure in the shape of a teepee. The tinder catches the spark. The kindling nurtures the flame. The logs fuel the fire. All the time we’re doing this in our minds. Every expectation is a bed of tinder. Our thoughts and emotions are the kindling that bears them flames. And our actions, those logs we toss into the flames, stoke little fires everywhere.

Now, fire has no intentions. No will of its own. The fire doesn’t care about how and where it starts, or what fuel you feed it. It only burns. It’s up to the builder to make the fire in a safe place. To tend to it. To keep it from blowing out entirely, or producing noxious and suffocating smoke, or even from raging out of control. If we build the fire properly and tend it well it can provide us with warmth and nourishment. But if we’re careless it will burn us. When many out of control fires converge everything burns. We do well to mind our fires carefully.

Choose good tinder by setting good non-negotiable standards for yourself. Allow positivity and realistic optimism to bear them flames. Feed the fire with wholesome actions. Ones that light up and warm your life. Not ones that reduce it to smoldering heaps of blame, resentment, anger, and self-pity. Use your non-negotiables to set you up for sustainable happiness by being pragmatic in forming them and reasonable in upholding them. Don’t expect others to do the same. Watch your life improve.

-Bryan

Summary

Expectations based on blame, criticism, and unhealthy comparisons lead to failure, resentment, and unhappiness. Our well-being is much better served by building our expectations upon a foundation of flexibility, appreciation, reflection, and compassion: the four pillars of well-being. Setting realistic well-being non-negotiables for ourselves according to these pillars leads to sustainable personal growth, greater happiness, and improved relationships with the people we meet and the food we eat. However, before we put the pillars into practice we need to recognize the difference between harmful and helpful expectations. Most harmful expectations materialize as blame-chains, formulated as if/then/should statements that build upon one another. Often they go unspoken, appearing instead in the form of internal dialog, and they often depend on some form of magical thinking. Any expectation may be considered harmful if they meet any of the following six criteria:

- They are rigid (e.g. the belief that oneself or others should never make mistakes).

- They are the product of magical thinking (e.g., “Person x should understand what I want without me having to tell them directly,” or “people should just be able to do what they’re supposed to do”).

- They are self-negating (e.g., demanding that all risks be eliminated before pursuing any undertaking leads one to pursue nothing at all, as absolute safety can never be guaranteed).

- They limit the full expression of thoughts and feelings of oneself or others (e.g., expecting that others never openly express anger or dissatisfaction).

- They presume an irrational degree of control over oneself, others, or events and circumstances. (e.g., insisting that one should never be late).

- They routinely lead to disappointment, disenchantment, or depression (e.g., expecting others to always be willing to apologize for perceived slights, or to recognize when we might be offended in any situation).

Key Points

- Flexibility is our foremost pillar of well-being. It is variable from person to person, but can be improved with practice. Try new things that put you outside your comfort zone one small step at a time.

- Appreciation has two equally important components: 1) gratitude for the things we might normally take for granted, 2) abstract understanding of our current state. Gratitude gives life meaning. Honest knowledge of where we are allows us to accurately envision what’s possible, which makes success attainable.

- Reflection is essential. Make time each day to reflect and unwind. The more you learn about yourself and the more honestly you assess your desires, the more reasonable your expectations will become.

- Compassion, especially self-compassion, is a key correlate of greater well-being. Practice patience, openness, and gentleness with yourself and others for improved relationships and life satisfaction.

- A non-negotiable expectation is a doable, maintainable, and realistic standard for our own well-being.

- You alone are responsible for your non-negotiables.

- Be flexible in defining your non-negotiables. For example, instead of I must workout every single day as a non-negotiable. Try, I will make exercise a weekly priority. Stick to 2-3 days a week at a particular duration for one month. After that, if you’ve maintained your new habit, try increasing the duration or sessions per week.

- Do not yield your well-being to unhealthy comparisons to those around you. The path is yours alone. Walk it with dignity and self-determination.